Article appeared in ECS magazine, Kathmandu, June 2012

By: Susan M. Griffith-Jones

The eminent religious historian Mircea Eliade once said, “The choice of holy space is not random but found and identified by the help of mysterious signs”.

This is absolutely true of the well known sacred site of Muktinath that on a superficial level may be seen as roughly a thousand square metres of temples, shrines, burial stupas, prayer wheels, natural springs, sacred trees along with other natural and man-made features imbued with supernatural characteristics reflecting both Buddhist and Hindu principles. Yet on a more abstract level, it may be interpreted as a working example of different religions sharing the same space with mutual respect.

Lying nestled at almost 4000m above sea level in the Trans-Himalayan district of Mustang, which is topographically part of the Tibetan plateau, Muktinath is one of the most famous pilgrimage sites in Nepal. For centuries, a major caravan route between India and Tibet has run along this dry and desert-like Trans-Himalayan upper path lined with caves that bear testament to another era of inhabitants.

To reach Muktinath from the plains, one must leave Pokhara, the nearest city to the Annapurna mountain range and the bright green rice fields of the valleys and foothills, behind. Subsequently spanning jungle and pine forests one passes through the Kali Gandaki, a huge, deep channel that cuts between the Annapurnas and Dhaulagiri, to emerge on the arid heights of the Tibetan plateau at an average of around 3000m.

Yet as the conventional rigmarole of modern and ancient ways of pilgrimages defines, both tourists with their cameras and backpacks as well as practitioners of Buddhism and Hinduism traditionally walk this arduous trail, a five to seven day journey from Beni on the lower Kali Gandaki. For the pilgrim it is mastering the road itself that will mean arriving at the sacred destination; for the tourist, it is a marvelous sight to wonder at.

The pilgrimage site of ‘Muktinath’, which is translated as ‘Place of Salvation’, is around 2000 years old, but the mountains of ‘Muktishetra’ – ‘Salvation Field’, which encompass the immediate area around the Muktinath valley and a little beyond, stem back about seventy million years to the Jurassic Period when this area was the seabed of the ocean of Tethis before the Himalayas rose.

Sources of many holy rivers such as the Ganges, Gandaki, Yamuna etc. flow from these mountains to India and for this reason, the area was always regarded as a holy land during the Vedic periods. Later when Buddhism entered Tibet from the 8th century onwards, the local people of border areas such as Mustang, who are of Tibetan origin also started regarding Muktinath as the site of Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig) and the tantric teacher, Guru Padmasambhava.

Sources of many holy rivers such as the Ganges, Gandaki, Yamuna etc. flow from these mountains to India and for this reason, the area was always regarded as a holy land during the Vedic periods. Later when Buddhism entered Tibet from the 8th century onwards, the local people of border areas such as Mustang, who are of Tibetan origin also started regarding Muktinath as the site of Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig) and the tantric teacher, Guru Padmasambhava.After Moghal influence started to increase in India both Hindu and Buddhist scholars began taking refuge in the Himalayas, thus the pilgrimage sites of this mountain range became more widely known. Traditionally both Hindus and Buddhists have their definitions and myths related to Muktinath.

A sacred Hindu temple made in a Nepali/Hindu pagoda style is situated at the top of the Muktinath valley and defines the place as its main feature. Even though there had already been some sort of a temple made of clay here prior to this, the present one was constructed around 1814 CE and renovated in 1929 CE.

For Hindu pilgrims, the central meaning of Muktinath is the veneration of their god, Vishnu. A four-armed statue of this deity that Nepali and Tibetan Himalayan Buddhists simultaneously worship as the compassionate Buddhist deity Avalokitesvara or Chenrezig, is contained within this temple. Another major attraction for Hindus is the possibility of receiving ‘darshan’, pure vision of the deity.

Some legends suggest how Vishnu, wishing to appear in this world in a form that could easily be worshipped and maintained by his devotees, took the form of sacred black stones or ammonites containing the fossils of prehistoric sea creatures, an extinct mollusk that once lived in the waters covering this region, their spiral shapes coiling into the stone’s centre. These particular stones are only found here in Muktishetra and should be left wholly intact with their inner designs hidden and thus power, unbroken.

Buddhist pilgrims have always been attracted to the simplicity of the place, where all five elements meet in harmonious effect. Water is universally associated with sacred sites and having special qualities here, is drunk by both Buddhists and Hindus in plenty. Muktinath is mentioned in Tibetan sources as far back as the 11th/12th centuries and is known locally as ‘Chumig-Gyatsa’ – ‘One Hundred and Eight Waters’ due to the 108 water pipes that circumambulate the main temple in a semi-circle. Water from the natural source behind the complex gushes from taps shaped as boars’ heads.

In ‘The Clear Mirror’, the Buddhist pilgrimage guide to Muktinath, amongst many other pieces of information, one reads that Mahasiddhas (great holy men) from India planted their walking staffs here that grew into poplar trees despite the high altitude and harsh weather conditions.

The traditional caretakers of Muktinath are around thirty Tibetan Buddhist nuns and in addition to the Hindu temple, there are three Buddhist gompas (temples) on the site. Under the altar of the ‘Jwala Mai – Temple of the Miraculous Fire’, natural blue flames burn. Originally there were three flames, one appearing on water, one on stone and one on earth. The latter expired around 50 years ago and for locals it is an ominous sign that things are changing. Here Hindu pilgrims venerate their god Brahma, who is believed to have set the water alight as an offering to Muktinath.Guru Padmasambhava, the great Indian Mahasiddha and one of the key figures to establish Buddhism in Tibet is believed to have visited Muktinath on his way to Tibet in 8th century AD. A formidable statue of him, reputedly made by his own hands, still stands in the Marme Lhakhang temple, another of the Buddhist gompas on the site.

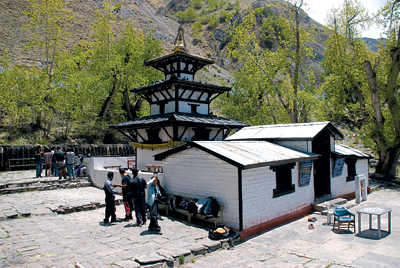

Situated just below the complex of Muktinath is the dharamshala of ‘Rani Pauwa’ – ‘Queen’s Resting Place’, now an expanded village of lodges and hotels for tourists. Its main feature is an old building that was once the quarters of royalty when they came to bathe in the sacred waters of Muktinath that provides resting space for pilgrims enduring the hard trip to Muktinath from all over Nepal and India.

Some make pilgrimage on foot from as far away as Southern India, whole families carrying their stoves and food for miles on end, weaving a chain towards their final destination. Rising at the crack of dawn, they prepare morning tea, do puja with many brightly coloured pigments of chalklike paste, sit in quiet meditation and bathe in the pools in front of the temple.

However, no matter who they are and where they come from, one aspect unites all people to this place, a unique energy of pilgrimage, of having endured many trials to reach it, of gathering the courage to continue to the end where some kind of relief, salvation or transcendence from the day-to-day sufferings of general life may await them.

For the general aim of pilgrimage, in styles both modern and ancient is to overcome the obstacles of the journey and reach the destination.