Appeared in VON, New Delhi, Oct 2016

By: Susan M. Griffith-Jones

For the devout, the Ganga is unpollutable

HAIL THE PURIFIER: Bathers in the Upper Ganga Canal at Har Ki Pairi in Haridwar

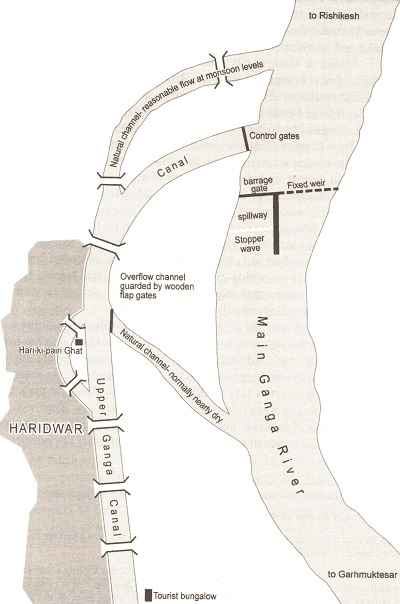

Ironically, for all the fame that precedes it, the Ganga town of Haridwar is not actually positioned upon her natural banks, but along the Upper Ganges Canal (UGC). The start of this British engineering feat of the 19th century is at the Bhimgoga Barrage near the Har-ki-Pauri ghat from where it draws out almost the entire flow of the Ganga’s water supply to go on to feed the hungry fields and homes of the North Indian ‘doab’ or ‘two rivers’, a vast area of land between the Ganga and Yamuna rivers.

The Ganga’s natural course, depleted and limping, continues a little way after Haridwar. This is her late youth. From here she is to become a worker in society, no longer tumbling carefree through the mountains as crystal clear streams virtually untouched by polluted hands, but enrolled in the needy day-to-day life of man as he too courses his path from cradle to grave.

DIVVYING UP GANGAJI: A map shows the lay of the canals

Although the UGC was initially proposed as a navigation canal, it was finally set up to irrigate land as far as Nanu in Aligarh district. The main canal is 290 kilometers long, but comprises important branches such as those of Kanpur and Etawah. There was neither an existing extensive canal system in the country or the world in the 1850s upon which to model the project or the work at commencement, nor a science of soil mechanics and hydraulic engineering to match soil type.

The brains of the project, Sir Proby Cautley, adopted the simple scheme of using the natural curves of nature and a compromising approach and, as a result, the reach of the canal from the head works to its 32nd kilometer may well be classified among the greatest feats of irrigation engineering in India. Indeed, the Solani Aqueduct that lies upon this stretch was ranked as one of the most remarkable massive structures of brick masonry in the world at the time.

The Lower Ganga Canal is 100 kilometers long and was sanctioned in 1872 to irrigate the lower portion of the Ganga-Yamuna doab. A weir across the Ganga at Narora, which is situated much farther down from Haridwar, does much of the work of sorting out her flow here; however, there are still large tracts of land suitable for agriculture, which do not yet have irrigation facilities and mostly lie arid.

A water scientist in Varanasi, Prof. UK Chaudhery, a retired professor of the Benares Hindu University, mentioned to me that from the Bhimgoga Barrage and onwards, “Ganga may be considered officially dead as 95% of water that is reduced from her flow in Haridwar is causing her the most dangerous blood cancer. Since there are two types of water in a river system—that which flows on the surface and the groundwater beneath, these must be balanced and flow smoothly together for the entire basin of the river to be in balance. This is not just a problem here on River Ganga, but throughout many river systems of today’s world.”

Indeed, as her natural path twists and turns across the land towards Kanpur, the many alluvial deposits found along the way cause islands of reeds and river plants to abound where historically dacoits and other bandits are said to have hidden out. Here huge fields of vegetables are tended to by folk from the sleepy villages that dot her banks, where people live virtually as they have for centuries.

These crops are now sprayed with the most deadly pesticides and chemical fertilizers to ensure a higher yield of harvest. This may be only for some past years, but the unknown truth of such use of chemicals upon naturally fertile soil is that it will finally deplete it of its ability to nourish itself, rendering it unsuitable for cultivation in the future. I think of the run-off into the ground water supply that Prof. Chaudhery had mentioned as 50% of the equation in the balance of the water supply of the river and shudder to think what enters her “bloodstream” from here onwards.

This stretch of the Ganga is Mahabharata land. Ferrymen carry locals to and fro across the river and back for a few rupees per person and life along the river goes on as it has since the time of the Pandavas. I have a feeling here of the ages stretching far into the distance, like layers of onion skin, encompassing the era of the Mahabharata and the ancient and medieval rulers of North India such as the Mauryas, the Mughals and, more recently, the British – layers of different cultures, religions and psychologies pooling into the genes of the people here.

But one story has remained like a golden thread throughout the ages and that is of the Ganga.

Today she is worshipped as she has been always, yet due to modernisation she is being abused in a different way, not only as a supply of water for a hugely increased population but “psychologically” as a patchwork of severed and pieced together sections between barrages and dams, canals and fertilized fields, with her entirety becoming fragmented and disunited.

After her furious pace through the mountains, you get the feeling that the Ganga enters a kind of lethargy where the natural course of her stream remains just a few feet at the most. There are many sandbanks and even though her course is wide in many places, often islands make her seem thinner and less voluptuous than she really is.

QUIETLY SHE FLOWS: Brijghat, 5km from Garhmukteshwar, is the nearest Ganga stopover from the capital

Brijghat is the nearest “Ganga” to Delhi, an hour and a half’s drive from the city, and weekends are busy here. The ghats are much cleaner and far less crowded in comparison to other places along the river’s course and Ganga devotees from afar come to bathe in her waters. Most famous for its annual Ganga fair, which is held every year on the full moon day in the month of Kartik, the ghats become like a mini-Varanasi, as thousands flock to take a dip.

Along the left bank is a large marble platform overlooking the river where stalls line the ghats, selling the usual Ganga paraphernalia; small white plastic jerry cans to take home your Gangajal, flowers to offer to the river goddess, powders of red, saffron and purple and even wood for the funeral pyre.

DAMMING’S HEAVY TOLL: Sand banks amid shallow waters near Brijghat

At the water’s edge, bobbing up and down, wait small boats that can take you to the nearest sandbank in the centre of the river where chai stalls and puja spots abound. The boats get stuck on several occasions while making the crossing, but Ganga devotees don’t mind. They simply jump overboard and seem to be walking on the water itself when you look at them from afar, paddling until they find enough depth to take a dip and to get the boat moving along naturally again. Shouts of joy and revelry resound amid these these activities.

It is clear that Hindu India loves the Ganga and nothing will dissuade them from enjoying her waters, no matter how much they are told about her levels of “pollution”. Pollution is a tricky word here as, technically speaking, as a goddess she can never be polluted and to say it may be to discredit her goddess status. She, who is believed to have the power to purify herself and anyone who comes into contact with her, can never be such in the eyes of devotees.

Scientific facts and water tests show otherwise, but the minds that exult in her goddess attributes seem to be unmoved.

Photos: Susan M. Griffith Jones